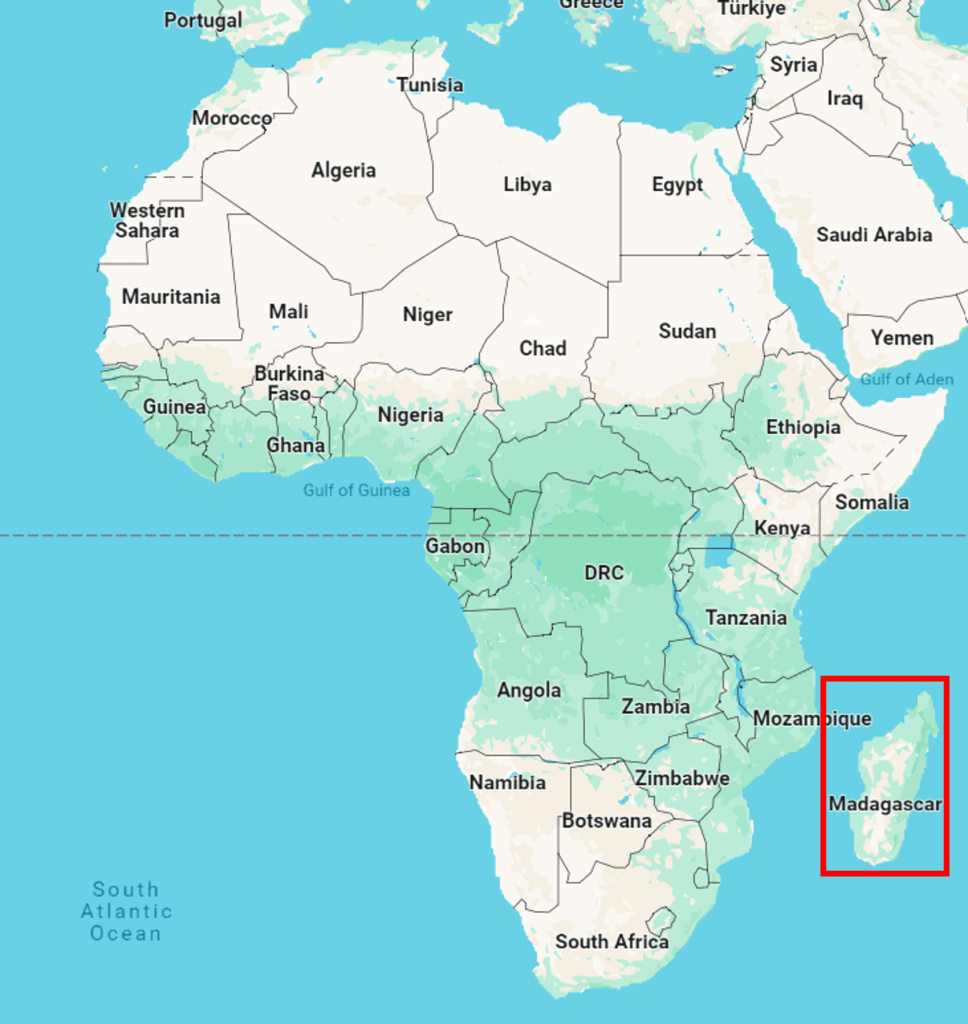

I went to Madagascar! If you are unsure where Madagascar is, it is the large island off the east coast of Africa. It is actually the fourth largest island in the world. After 1. Greenland, 2. New Guinea, and 3. Borneo. If you are thinking, “But isn’t Australia bigger than all of those?” Yes, it is but Australia isn’t considered an island because it is a continent. Madagascar is also the home of King Julien in the animated DreamWorks movie Madagascar (2005).

I spent four weeks in Madagascar. I was a Lemur and Wildlife Conservation Volunteer with an organization called GVI (1,2). Here is the link to the GVI homepage if you want to check it out.

I have been back from Madagascar for about three weeks now and have reflected a lot on my time there. I wanted to share an overview of my experience. First, I don’t have the perfect words to describe this experience, either culturally or environmentally. Here is my attempt: it felt unreal, eye-opening, wonderful, fulfilling, beautiful, and, at times, intimidating. Does anyone have the word that I am looking for to describe experiencing all of those feelings at one time?

Introduction to Conservation in Madagascar

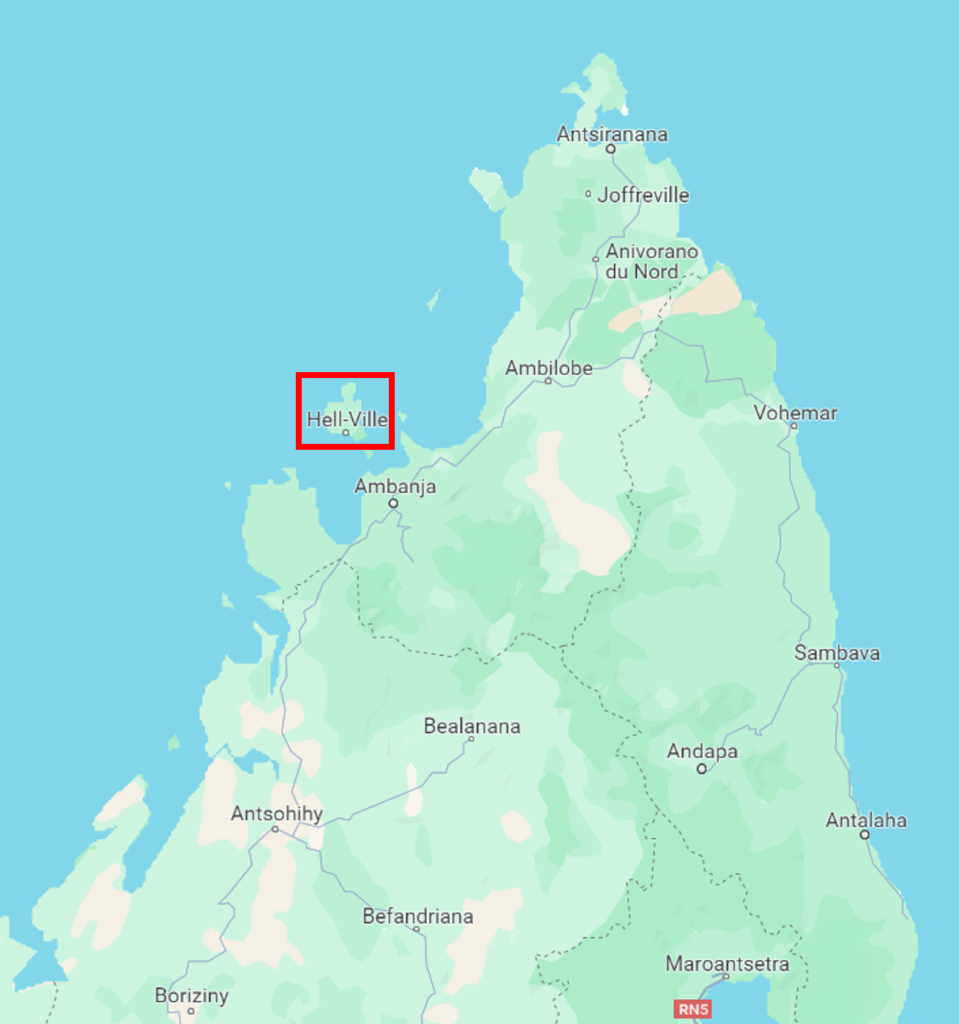

As a conservation volunteer with GVI Madagascar (2), I worked with local experts. Conservation volunteers work in and around Lokobe National Park (3). We conduct Lemur Behavior Surveys, Herpetology (amphibians and reptiles) Transect Surveys, and Bird Point Counts. We also work with Park Rangers to help them develop their English-speaking skills. They use these skills to provide more efficient tours to English-speaking guests.

The animals… What can I say about seeing the animals in the most unique place on Earth? Almost all of the animals here are endemic. This means they aren’t found anywhere else in the world. For instance, Madagascar is the only place where lemurs live in the wild. At the same time, you will not find any apes, monkeys, gorillas, bonobos, or orangutans in Madagascar. The only primates that currently live in Madagascar are lemurs and humans, the first of these being the only native primate to Madagascar.

Seeing these animal, every single day was amazing! I will share more about my conservation experience and the details of each survey type in another article.

Community Work in Madagascar

GVI offers both Conservation programs and Community programs (1). In Madagascar, the Community and Conservation volunteers live and work at the same base (2). Therefore, I saw what the Community team did and heard what their experiences were like.

The Community team works with local children and adults to help them learn English. The main languages in Madagascar are Malagasy, followed by French. Madagascar used to be a French colony until the 26th of June, 1960. I was there during their 64th Independence Day celebration.

There has been an increase in English-speaking tourists. As such, providing English lessons helps locals communicate their services. It also helps Malagasy people and English-speaking tourists have pleasant conversations. I enjoyed walking through town and hearing many children and adults talk to us using the English they learned. Also, all GVI Madagascar volunteers have weekly Malagasy language lessons. When possible, I used these lessons to communicate with locals in their preferred language.

Life in Madagascar

Madagascar ranks as a country that experiences one of the highest rates of poverty. Depending on what financial scale is being used, I’ve seen it ranked as the 3rd to 9th poorest country in the world (4,5). As such, the experience of living there for a month was unique. Before joining the program, this was also a point where my brain wondered, “Is it beneficial for me, and the other volunteers from developed countries, to come to Madagascar and volunteer? Were the communities and the National Park getting as many benefits from us being there as we were?” Yes, I do believe so.

The GVI Program Manager, Rojo, and many of the staff are local. They have lived in Madagascar their entire life. Several of them actually built the GVI base two years prior, which was when the program first started. This tells me they want the program! Also, from what I can tell, they enjoy having us there and working with us. The local staff share their knowledge of the community and culture with us. So we aren’t only tourists doing a little volunteer work on the side. We focus on learning and volunteering. Then on weekends we do enjoy a little of the tourist activities.

Furthermore, the base we live at while volunteering is not a fancy tourist hotel; we stay in dorms/huts. The roofs are made from palms and the walls are made from the tree trunk and/or branches. Our two showers and two toilets are also all in one hut. They have walls dividing these four facilities from the ground to about three fourths of the way up. The top of this hut is a space without dividers so that air can flow through. The shower temperature is either cold or colder, depending on the time of day.

The toilet/shower hut also has a frog who enjoys hanging out there. It is a Dumeril’s bright-eyed frog (Boophis tephraeomystax). It is affectionately called Toilet Frog. I was blessed by visits from Toilet Frog several times.

People who live in Madagascar are accustomed to the water and can drink from the taps. However, if you drink tap water in Madagascar, you will likely get sick. So at base, we have one outdoor water tap that has a filter on it so that we always have drinkable water. We have another water tap we use for washing laundry by hand. Don’t mix them up though, the tap for laundry does not have a filter!

Outside of our base is the road that goes around the island. Tuk-tuks, a small three-wheeled vehicle, are the typical taxis in Madagascar. They drive past and we hop in, often sharing them with locals who are also heading somewhere.

For the most part, the locals are very friendly and accommodating. When walking around they greeted us with “mbala tsara!” (“hello” in Malagasy). When I would say “mbala tsara”, many locals would chuckle. Was it my accent? I was told it was because they were happy to hear a tourist speak in Malagasy. In the end, I felt safer walking around by myself on Nosy Be, Madagascar than I have in some places I have lived in the United States.

I recommend GVI to anyone interested in immersing themselves in local culture while volunteering for the community or conservation. I also think it’s a great experience for anyone interested in a unique international and educational experience. My experience was rewarding and beneficial to my lifelong learning. Next, I have my eyes on a 4-6 month GVI program in Kekoldi, Costa Rica where I can work with sea turtles (6).

Citations

- “Volunteer Abroad” (On-line) GVI Homepage. Accessed in 2024 at https://www.gviusa.com/.

- “Volunteer in Madagascar” (On-line) GVI Madagascar Homepage. Accessed in 2024 at https://www.gviusa.com/volunteer-in-madagascar/.

- “Lokobe, A Preserved Primitive Forest” (On-line) Madagascar Treasure Island Nosy Be. Accessed in 2024 at https://nosybe-tourisme.com/en/discover/nosy-be/lokobe-natural-reserve.

- “Poverty headcount ratio at national poverty lines (% of population)” (On-line) World Bank Group. Accessed in 2024 at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.NAHC?view=map&year_high_desc=true.

- “IMF Staff Country Reports: Republic of Madagascar” (On-line) International Monetary Fund. Accessed in 2024 at https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2023/03/21/Republic-of-Madagascar-2022-Article-IV-Consultation-Third-Review-Under-The-Extended-Credit-531196.

- “Volunteer in Costa Rica” (On-line) GVI Costa Rica Homepage. Accessed in 2024 at https://www.gviusa.com/volunteer-in-costa-rica/.