The Background The You Should Know

From the 14th March, 2025 to the 2nd August, 2025, I was in Costa Rica as a Sea Turtle and Wildlife Conservation Intern. As part of my internship, I participated in 12 km (~7.4 miles) beach walks at night and in the early morning. At night we searched for sea turtles coming up to the beach to nest. In the morning, we searched for nests that were laid after the night survey ended. When we found a sea turtle nest, we used our hands to gently unbury the eggs and then move them to a bag, one egg at a time. We held them tenderly and without rotating them so we wouldn’t cause harm to the developing babies inside. We then gently carried the bag of eggs to our nursery and reburied the eggs in an incubator.

There are multiple reasons why we moved the sea turtle nests to an incubator. The two main reasons being: (1) Illegal poaching and (2) microplastic pollution on the beach. Poachers dig up sea turtle nests on the beach to collect the eggs. They will then eat the eggs raw or sell them to others who want to eat them raw. They believe a raw sea turtle egg is an aphrodisiac. If a sea turtle nest is left on the beach the poachers will take all of the fertilized eggs for themselves and none of the babies will survive. Secondly, microplastics in the sand will cause the sand to heat up too much and eggs won’t survive the high temperatures or the ones that do survive will become all female turtles. This is because the gender of sea turtles (and many other reptiles) is determined by the temperature during their incubation period. For sea turtles temperatures above 29◦C (~84◦F) will become female turtles. Temperatures below 29◦C (~84◦F) will lead to male turtles. Temperatures at 29◦C (~84◦F) will become a mix of male and female turtles. In order for sea turtle populations to continue on we need both male and female turtles.

There are seven species of sea turtles worldwide. Three of these species can nest in the area of Costa Rica that I worked in. These are Leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea), Green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas), and Hawksbill sea turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata). When I first arrived in Costa Rica, in March, the main turtles nesting during that time were the leatherback sea turtles. Leatherbacks are the largest of the seven sea turtle species with a shell length up to 190 centimeters (~75 inches). This length doesn’t even include the head or tail! They also weigh up to 700 kilograms (~1,500 pounds), this does include the head and tail, and every other part of the turtle. They also are the only sea turtle with a soft “leathery” shell instead of a hard shell. This soft shell allows them to dive deep, up to 2,000 meters (~6,562 feet), into the sea for food. The first time I saw an adult on the beach it felt as though time could stop. She was so majestic and beautiful. I can’t even put into words how it felt seeing her laying her eggs, covering them up, then throwing sand around the area surrounding her nest to camouflage her nest.

Finally: The Turtley Awesome Story

Anyway, here is my story of the first turtle nest I helped relocate on March 26th, 2025. It began during my second week in Costa Rica, and I definitely think this should be the next Pixar short. Early in the morning on the 26th of March we got a message that a new leatherback nest was found and we needed to help locate the eggs and then move them to the nursery. Sea turtles camouflage the area of their nest after laying their eggs to make it harder for predators to find. This can also make it harder for us to locate the egg chamber in order to move the eggs to safety.

We got ready as quickly as we could and walked the 4.7 km (~2.9 miles) to where the nest was found. It took us awhile to locate where the nest most likely was and then we started gently digging with our hands. After a short time of digging, we started finding vanos eggs. These are unfertilized eggs that a leatherback sea turtle lays after she has laid her fertilized eggs. These will then sit at the top of the fertilized eggs so if an animal finds and digs up the nest they would eat the unfertilized eggs and get full before they find the actual fertilized eggs. These vanos/ unfertilized eggs could never develop or hatch into a turtle. In fact, they only have egg white, no yolk within the egg. Poachers usually do not collect the vanos eggs as they don’t contain what they want to eat.

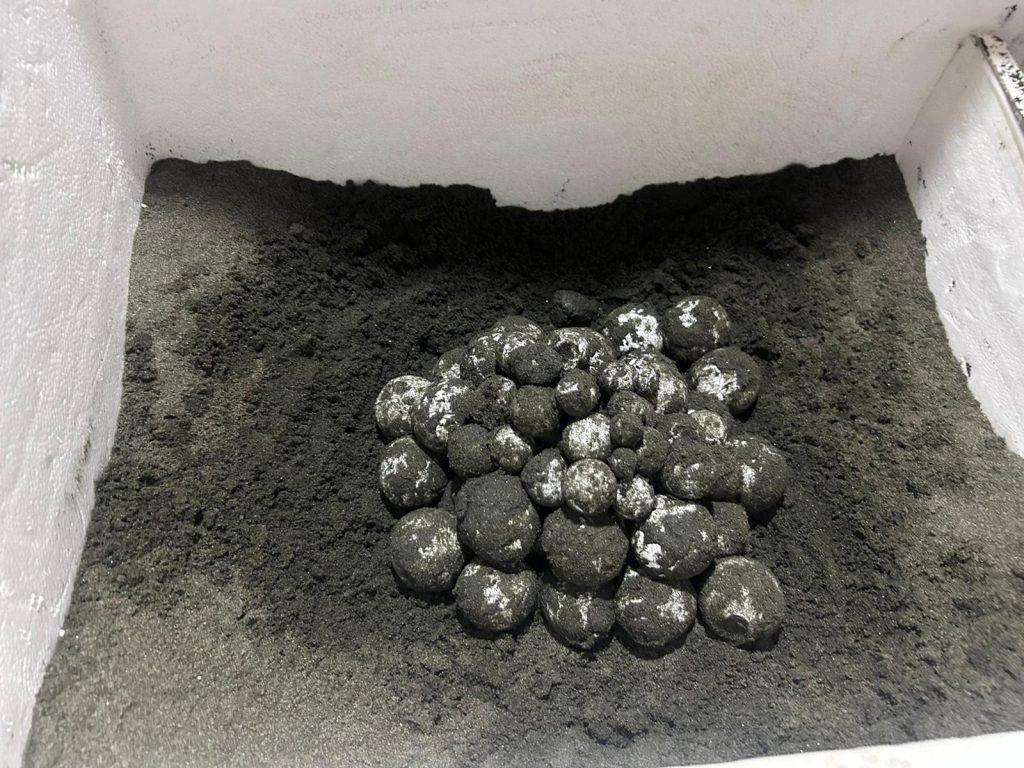

To keep the integrity of the nest when we relocate it to the incubator, we collect these vano/unfertilized eggs along with the fertilized eggs. We then place the eggs in the incubator in the same way they were on the beach: fertilized eggs on the bottom, vanos eggs on top, then covered with sand.

As we moved these vanos eggs to the relocation bag and dug for more eggs we finally came to the first fertilized egg. I was excited as this was my first ever sea turtle nest and therefore, my first sea turtle egg! We kept moving the sand and eventually came to the bottom of the nest without uncovering anymore fertilized eggs. As we sifted through the sand, we realized that the nest had been illegally poached and somehow the poachers missed one fertilized egg among the vanos/unfertilized eggs that they didn’t want.

We still had hope for this one egg so we relocated it along with the 52 vanos eggs to our nursery where we buried them in a nest with cleaned sand in an incubator.

Here is where we wait. Typically, leatherback sea turtle eggs can take 60-75 days to develop while in an incubator. Five days after a nest hatches, we dig up the fertilized eggs that didn’t hatch so we can see at what stage they stopped developing and if they had any bacterial or fungal infections that stopped them from developing. It is normal to have a portion of fertilized eggs, within each nest, that don’t hatch. In fact, leatherbacks have the lowest hatching rate of any other sea turtle. Research has shown that in the wild usually only 50% of fertilized eggs hatch.1,2

As we hit 60 days after we relocated our one egg to the nursery, we kept thinking about it, hoping the baby turtle would hatch. Eventually 75 days rolled past and the baby turtle still hadn’t emerged. I still had hope but also concern.

Finally, 91 days passed and it was time to admit the sad outcome that our one fertilized egg didn’t make it. We started digging up the nest so we could check when the egg stopped developing and look for signs of infections.

To our surprise the egg was cracked we could see movement from inside the egg. We could tell that she was not developed enough to be released into the sea yet. We were concerned that we took the egg out of the incubator nest too soon even though it was well past the typical 60 – 75 day duration for hatching. We hadn’t removed her from her egg though so we gently placed her egg back in the incubator and covered it lightly with sand. We still had hope for her to continue developing, leave her egg, and crawl above the sand but we also knew with a damaged egg she may not make it. Side note, we keep the nests around 29◦C so this egg could have been developing as a male or female but I am going to refer to the baby turtle as a “she” from here on out.

Three days later, 94 days after we found her egg alone in a poached nest, she had reabsorbed all of her yolk (what all eggbound babies feed off while in the egg and for a short time after hatching) and pushed herself out of her egg and up through the sand covering the egg within the incubator. She was ready to make the journey to the sea!

We weighed and measured her, then took her to the beach where her nest originally was laid. We set her down on the sand far enough from the sea because she needed to orient herself and crawl to the water on her own. This first journey to the sea helps sea turtles build up the muscles they will need in order to make the rest of their journey. In addition, it is believed that this is when the beach imprints on the turtles so they know where to come back to when it is time for them to lay their own nests, if they are female. She started her slow crawl over the sand, seeming unsure what she was supposed to be doing. However, as soon as a wave came up and around her, she felt and tasted the sea for the first time and her instincts kicked in. She began swimming for the first time. We saw her pop her little head up above the water to take her first breath of air from the sea and then dove down to begin her life under the waves.

Citations

Fatungase, F.O. (2025). Nesting Ecology of the Leatherback Turtle, Dermochelys coriacea, at Estaciόn Las Tortugas, Costa Rica: 2013-2021 and 2024. Master of Science Thesis at Purdue University: 1-40.1

Picknell, A., K.M. Stewart, K.R. Stewart, and M.M. Dennis (2024). Assessment of Hatching Success, Developmental Phases, and Pathology of Leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea) Embryos and Dead-in-Nest Hatching on St. Croix, US Virgin Islands. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 23(1): 103-112.2